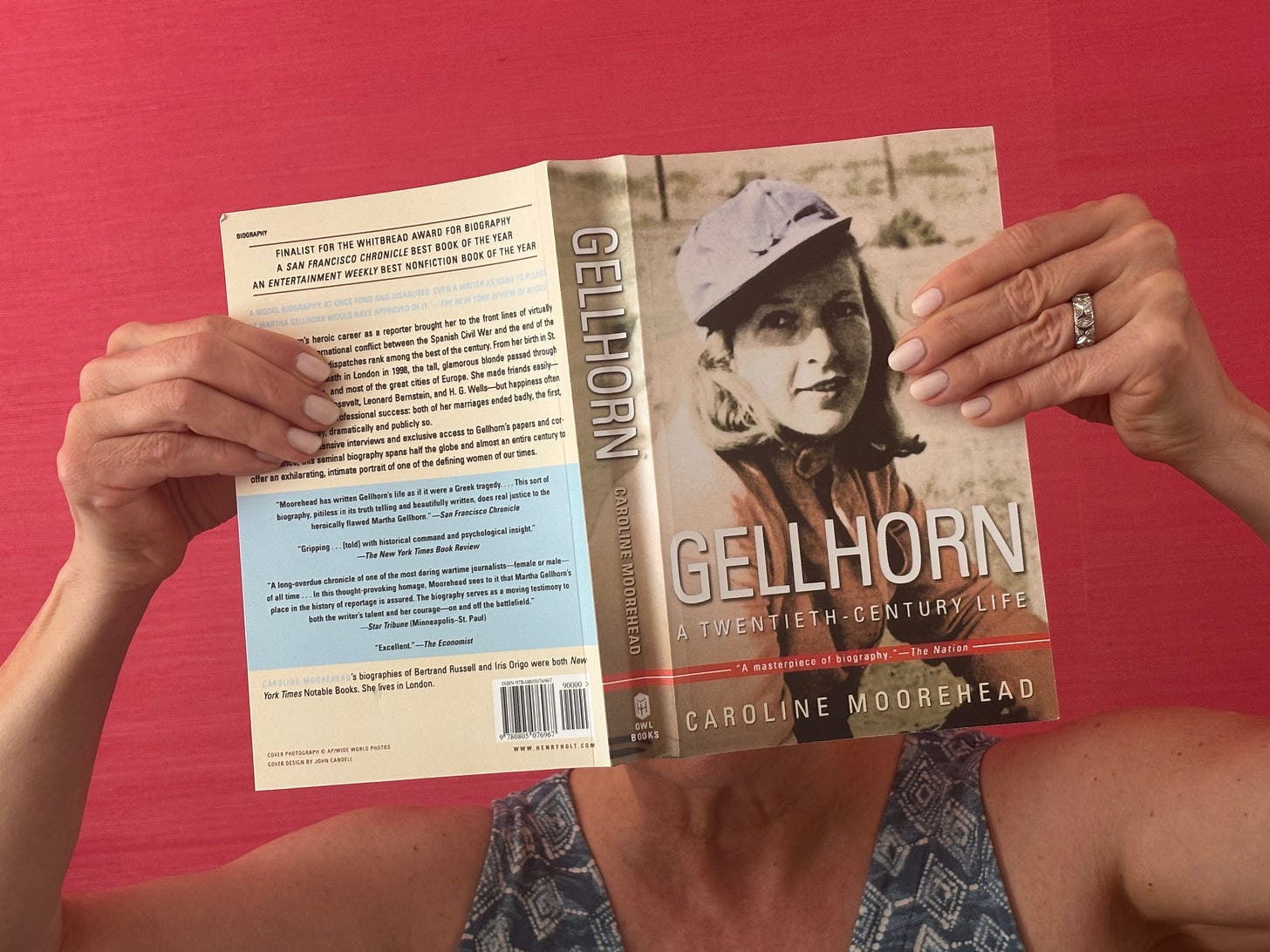

I’m so excited to introduce you to our inaugural Radical Women Book Club pick: Gellhorn: A Twentieth-Century Life by Caroline Moorehead.

After returning from documenting the Spanish Civil War (her first), journalist Martha Gellhorn spoke to the 3500 (mostly male) attendees at the Second Congress of American Writers at Carnegie Hall about the belief system she carried for the rest of her life:

“A writer must be a man of action now…a man who…has given a year of his life to steel strikes, or to the unemployed, or to the problems of racial prejudice, has not lost or wasted time. He is a man who has known where he belonged. If you should survive such action, what you have to say about it afterwards is the truth, is necessary and real, and it will last.”

She was a study in contrasts:

Born into privilege—but building a journalist career traveling to global hotspots to document the horrors of war.

Possessing boundless compassion for those suffering from the effects of war—but zero patience with anyone who bored her.

Craving intimate connections with her chosen circle—but cruelly eviscerating those who disappointed her.

Comfortable with hordes of people in the midst of danger—but nurturing a deep hunger for being alone.

A tall, striking woman with a deadly wit, war correspondent, writer and author Martha Gellhorn did not suffer fools—in fact, she called them out, sometimes mercilessly.

Born in a time when gutsy women were to be shunned rather than embraced, she forged a brave career speaking truth to power.

Her privileged upbringing would deliver great gifts, such as access to First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt (a sorority sister of her mother’s), that led to her bunking at the White House during the Depression.

But those gifts came attached to a constant internal and external fight against society’s expectations for a well brought up young woman: she spent the rest of her life radically fighting convention and injustice.

“I had a theory that you can do anything you like if you are willing to pay the full price for it.”

She did—and she was.

Her war experiences kicked off in Spain, partly because of Ernest Hemingway’s plans to report on the Civil War (they’d just begun a romance after meeting in Key West) and partly after hearing the Nazis (whom she’d despised since the early 1930’s) call the Spanish loyalists the “Red Swine dogs of Spain.”

It was in Spain where she first dealt with both the desperation and inconveniences of war and found herself moved.

“We knew, we just knew that Spain was the place to stop Fascism. It was one of those moments in history when there was no doubt.”

She became a fearless witness: reporting on bombs dropped and body counts, but always looking for the ordinary human story.

While in Spain, Gellhorn visited the front and the aftermaths of battle multiple times; she toured hospitals, observing and interviewing nurses and patients. She went shopping to understand what was on the shelves, visited the zoo and a sewing factory and accompanied a doctor bringing blood transfusions to the front. Her hotel was bombed.

But she didn’t write anything for a few weeks after arriving—instead, she protested to Hemingway when he suggested she write a piece for Collier’s that “she knew nothing about war or military matters, only about ordinary people doing ordinary things.”

Then she decided to submit an article about an old woman trying to protect a young boy who was killed by a shell while walking in the street. Collier’s not only bought that piece but put her name on its masthead when she submitted a second. Then the New Yorker took two other articles.

She was officially a war correspondent.

Two themes ran throughout her adult life after Spain: an almost desperate commitment to be that fearless witness when war muddied the truth and a deep desire to find a peaceful, interesting existence away from that.

I couldn’t help but wonder if Gellhorn didn’t have what we now call ADHD—her constant need to keep moving, keep advancing on multiple fronts reads a bit like the challenges of a busy brain.

And yet, what a perfect constitution for a war correspondent in the midst of multiple conflicts. Her foreign travels (after landing in Paris and writing fashion articles as a freelancer) began at the 1930 League of Nations convention in Geneva where she wrote about the top female delegates.

She interviewed Fascists and Nazis in pre-war Germany and—after Spain—hopscotched around European hot spots during World War II, writing well-received pieces for a who’s who of serious news publications.

Gellhorn introduced a new style of war journalism: stories that focus on everyday people in ordinary and extraordinary circumstances.

She became the only woman at the Normandy beach landing by sneaking onto a hospital ship and impersonating a nurse, because the military refused to grant women permission to travel to the front.

She was stripped of her correspondent’s status and arrested, although she was quickly released and flew on to Italy. Later, she was one of the first journalists to report from the Dachau concentration camp.

Gellhorn found no peace at the end of the war, but rather a fire to continue documenting injustice and telling real stories while holding governments and politicians accountable.

“It is unbearable to realise the effort and the pain of others and not be part of it. I think of the countries we have known and loved as if they were people being killed.”

She protested McCarthyism and reported extensively on the Vietnam War, various Arab-Israeli conflicts, civil wars in Central America and the U.S. invasion of Panama. She worked into her 80’s, leaning into a renaissance as a younger generation discovered her books and activism.

She had an unsatisfying short marriage to Hemingway (knowing his history, I couldn’t help letting out a “noooooo” when she decides to marry him). As his third wife—the only one to leave him—she refused to allow her story to be dominated by Hemingway or his legend. Instead, she declined to participate in any public mention of their names together.

One piece of her life that tugs at the heart is her adopted son Sandy. Her natural inclination was not one of nurture, so she struggled to raise him once he grew into his teens.

Their relationship was like so many others that challenged Gellhorn—people inevitably disappointed her and she struck back. It took a strong constitution to love and be loved by her.

Just like powerful men, Gellhorn was never just one thing.

She could be an exquisite listener—curious, insightful, witty and charming. She cared deeply about the future and preventing conflicts from becoming wars. She built multi-layered relationships with other writers, world leaders and fellow activists. She created homey nests for herself, her child and stepsons and could be fiercely protective. She worked a lifetime honing her craft, despite finding writing a painful grind.

All told, Gellhorn lived as a Radical Woman—using her privilege to protest and to bear witness while changing modern journalism to focus on the human cost of conflict.

You can find the book at your local independent bookstore or use this link to my bookstore page which supports independent book sellers.

Stay tuned for discussion prompts (paid subscribers can jump into the community discussion), but feel free to comment on (or share) this post anytime…

Cheers,

Rochelle